The Hidden Messiah In Judaism

By Richard Harvey, Academic Dean, All Nations Christian College, UK

Introduction

The doctrine of the Messiah is, alongside those of God, Torah and Israel, a fundamental and essential teaching in Judaism. Hope for the Messiah's appearance has been the major focus and driving force behind Jewish religious belief and behaviour over the millennia.

Whilst this messianic expectation has helped to preserve the Jewish people throughout history, there have always been conflicting opinions about the messiah's appearance, identity, and the

implications of his coming.

Whilst the Messianic concept is fundamental to Judaism, and especially to that form of Messianic Judaism which believes in the Messianic claims of Yeshua (Jesus), it is no easy task to describe the development of this concept, not least the aspect of the 'Hiddenness' of the Messiah.

This paper will not focus on all aspects of the doctrine of the Messiah but present a historical survey of the 'Hidden Messiah'. It will highlight some of the theological and missiological questions that arise for those of us who proclaim that the hidden Messiah is now revealed, and that we have a responsibility and joy in sharing Him with the people of Israel today. The importance of the subject will be obvious – if the Messiah is already present, already hidden amongst his people, what need is there to proclaim him?

The hiddenness of God

We should remember that in one sense, God himself is hidden from us. No eye can see him, and no ear can hear him speak, unless He chooses to reveal Himself to us. We can discern his presence through creation, we can know his designer's hand behind the order of the universe, and we can sense his purposes through watching the divine watchmakers instrument at work, but his essential nature remains hidden.

We can understand something of his character, concerns and values through our own consciences, and through the moral judgments that we make between right and wrong. But we can not know Him, can not

peer behind the veil that hides Him, unless He chooses to reveal Himself to us. Even the fact of His existence is hidden from us. We can only know it and believe in Him when He chooses to reveal

Himself to us. The God who is beyond our human dimensions of time and space is hidden from view, from knowledge, from understanding unless He graciously and powerfully speaks his word into our hearts

and minds, and we receive His revelation. In scripture, the word for revelation is galah -not just to reveal but to uncover, to pull back the curtain, to make obvious what was hidden from view. In

Greek, apocalyptein – to cover, apocalyptein – to uncover, apocalypse, and uncovering. Without revelation God himself is hidden, remains hidden and will not be known or understood. And even when He

does reveal Himself, through creation, through providence, through our consciences, and ultimately through His Word, there is still more that is hidden, that we will never know this side of

heaven.

God's Word reveals God. The Scriptures, the written Word of God, witness to the Messiah, the Living Word of God the Son. The Church, the Body of Christ, has the responsibility to preach this Living Word. God speaks, and it is so. God speaks, and there is light. Revelation. Unhiddenness. So as we recognise something mysterious about the hiddenness of God which is now graciously revealed, let us see how the Messiah shares in both the hiddenness and revealedness of God himself. We can then know Him personally, as Father, Judge, Shepherd, King, Friend and Saviour.

The hidden Messiah of the Tanakh

‘All the prophets spoke only of the days of the Messiah’ say the Rabbis (B. Berakot 34b). When we read the Hebrew Scriptures typologically and christologically, there is abundant evidence for the Messiah in the Tanach. The first believers in Yeshua (Jesus) used the same interpretive approaches and exegetical devices.

So the doctrine of the Messiah is implicit, rather than explicit. Levitical religion uses the term ‘Messiah’ infrequently and inconsistently. The doctrine of an eschatological redeemer can be constructed from such passages, and Messianic prophecy points to the coming of such a figure, but the picture is only clearly seen in the light of Yeshua (Jesus), and his own explanation and self-definition. The Tanach, particularly the prophets, sees the coming of the Messiah in the light of apocalyptic expectation of a redeemer, but his identity, mission and arrival are hidden in the future, in a complex of eschatological events such as the Day of the Lord, the restoration from Exile and the Judgment of the Nations.

There is no clear picture, and we are left to ponder a mystery.

The Day of the LORD includes judgment against foreign nations, against Israel, and the promise of future deliverance and blessing for Israel, the nations, and all creation. The Divine Rule of YHWH will be inaugurated quickly and decisively with military intervention. The Kingdom will be restored to the Davidic King, who will be enthroned in Jerusalem in a time of peace, justice, fertility and covenant obedience. But there is also the hiddenness of the servant, despised, rejected, scorned and betrayed, as Israel is herself in Exile, the mockery of the nations. It is from here that later understandings of the Hidden Messiah develop.

The hidden Messiah of inter-testamental Judaism

In the scriptures, the term maschiach refers to individuals with a divine mission such as prophets, priests and kings. The prophets compared corrupt leaders with the belief in an ideal, divinely ordained, righteous king. In post-exilic literature, the Messianic king is God's agent who will vanquish Israel's enemies and establish a reign of peace.

When the Babylonian exiles returned, Zerubbabel (6th c. BCE) is seen in Messianic terms. The Maccabean revolt against the Seleucids (2nd c. BCE) has messianic overtones, and a number of Messianic

sects emerge during the Hellenistic period. The DSS community expected the appearance of two Messiahs (a Messianic king and high priest) whereas other groups expected a suffering servant or

transcendental deliverer.

War against Rome is seen as eschatological struggle that would result in the advent of the Messianic age. After the destruction of the Temple in 70ce some interpreted the calamity as the birth-pangs of the Messiah. In the Bar Kochba revolt, Akiba proclaims him Messiah. The concept of a warrior who would die in an eschatological battle became part of Jewish thought.

When he discusses the hidden Messiah, Mowinckel musters evidence from such diverse texts as Justin Martyr, 2 Esdras, the Gospel of John, Midrash Tehillim, the Targumim, and Revelation. But why must the Messiah be "hidden"?

Mowinckel answers this most central of all questions thus:

This is probably how most Jews would have answered the question. Sufficient penance has not yet been done for the sins of Israel; and until there is genuine conversion and obedience to the Law, the Messiah cannot 'be revealed'. That is precisely the reason why first of all there must come men who can evoke penitence and conversion, and put all things in order, namely those forerunners of the Messiah to whom we have referred. (Mowinckel 2005: 308)

The hidden Messiah of the New Testament

Yeshua (Jesus) himself keeps his Messiahship secret at various stages of his ministry. It is only after his resurrection, on the Emmaus road, that he begins with Moses and all the prophets and expounds to his disciples the 'things concerning Himself' in all the Scriptures (Luke 24:27).

These truths have been hidden from them until 'he opened their understanding, that they might comprehend the Scriptures' (Luke 24:45). His use of secrecy in Mark's Gospel is well-know, and from the time of William Wrede scholars have attempted to explain his commands to keep silent after miracles, the silencing of demons, and his commands that the disciples not make known his identity. He speaks in parables (Mark.4:10-12) to hide his identity.

The hidden Messiah of the Mishnaic system

With the onset of Rabbinic Judaism the Hidden Messiah plays one part in a complex picture of Messianic expectation. It is not possible to derive a fixed and coherent picture of messianism from the Hebrew Bible. ‘In early Jewish literature, the term ‘messiah’ is notable primarily for its indeterminacy’ (Scott Green 2000:253). Catastrophe, salvation and restoration are projected onto contemporary events.

The ideal is projected into the future. Events take place in one world – the world we know. All events will be realised visibly for everyone in this world. The time that precedes judgment and salvation runs directly into the time of national and political restoration of the people of Israel. The Day of the Lord is both the same and separate from the Last Judgement. The biblical concept of salvation not just individual but communal and applies to whole nation. The expectation that the time of the former glory of Israel will return can be characterised as restorative: people looking back into the past and expect the restoration of everything that was lost. In contrast with this there stands the expectation that in the future something will be realised that has never previously taken place. This way of looking to the future can be characterised as utopian.

There has always been a tension between what Gershon Scholem called restorative and utopian visions of the future. Restorative and utopian elements not strictly distinguishable. In the visions of the future one finds both the restoration of everything that has been lost, and elements that have never been realised. The Messiah is the missing piece in the speculation about the end times, but the doctrine of the Messiah is not a unified one. His hiddenness allows for uncertainty, ambiguity and puts the attention on other factors such as Israel’s repentance, the wickedness of the nations, and the contrast between this world and the world to come.

The Messiah is ‘hidden in the womb of Time’, pre-existent with God. His preexistent hiddenness shows him to be more than just a mortal, but one who has a ringside seat awaiting the moment when God will send him into action to accomplish Israel’s salvation.

Seven things were created before the word was created: The Torah, Repentance, the Garden of Eden, Gehenna, the Throne of Glory, the Temple, and the name of the Messiah….The name of the Messiah, as it is said: May his name endure forever, may his name blossom before the sun (Ps. 72:17). (B. Pes. 54a, B. Ned. 39a in Patai 1979:19)

The Name of the Messiah is linked to the verse on which his pre-existence is based, Ps. 72:17: ‘His name burgeoned before ever the sun was’. Several sources enumerate four or six or seven things that preceded the creation of the world. ‘The name of the Messiah’ may be used instead of ‘the Messiah’ as an intentional change for anti-Christian polemical reasons. Nevertheless, the pre-existence implies the Messiah is hidden behind the scenes, awaiting his moment.

And there I saw him, who is the Head of Days, And his head was white like wool, And with him was another one whose countenance had the appearance of a man And his face was full of graciousness, like one of the holy angels. And I asked the angel who went with me and showed me all the hidden things about that Son of Man: Who is he and whence is he, and why did he go with the Head of Days? And he answered and said to me: This is the Son of Man who has righteousness, With whom dwells righteousness, And who reveals all the treasures of the crowns, For the Lord of Spirits chose him… (1 Enoch 46:1-3 in Patai 1979:18).

He is hidden so that he shall be revealed to the elect at the right time. From the beginning the Son of Man was hidden, And the Most High has preserved him In the presence of his might And revealed him to the elect. And the congregation of the elect and the holy shall be sown, And all the elect shall stand before him on that day. And all the kings and the mighty and the exalted and the rulers of the earth Shall fall down before him on their faces, And worship and set their hope upon the Son of Man And petition him and ask for mercy at his hands (1 Enoch 62:7-9 in Patai 1979:18-19).

In the apocalyptic literature ‘hidden’ is the term ascribed to the Messiah in referring to the period before his revelation. In the Book of Zerubbabel, the angel shows Zerubbabel the David Messiah sitting in Rome and tells him: ‘This is the Messiah of the Lord, who is hidden here until the time of the End.’ (Patai 1979:111: ganuz berakat, ‘hidden in Rakat’, Tiberius: D Stern and M Mirsky, eds. Rabbinic Fantasies (Phila-NY, 1990: 67-90).

The Messiah is hidden in the clouds, as Daniel’s ‘Son of Man’, but will reveal himself at the right time. His name is ‘Anani’ – he of the clouds.

Anani (‘He of the clouds) is the King Messiah, who will in the future reveal himself (Targum to 1 Chronicles: in Patai 1979: 83).

The hidden Messiah of Talmudic speculation

The Messiah is hidden, not just in apocalyptic speculation, but in rabbinic justification of the Mishnaic system. The Messiah becomes the teleological justification of the Mishnaic system of purity, and the Talmudic discussion of the Messiah's name, nature, comings and destiny is inconclusive. It is not a central doctrine, but is 'secondary to the major and generative categories of the rabbinic system' (Green 2000:255).

In general terms, the Talmudic understanding of the Messiah is that he will come at a time of trouble and oppression for the Jewish people and subdue Israel's enemies. The time of his coming is known

to God, but can be hastened or delayed it by Israel's state. Repentance and obedience to Torah can hasten redemption. The Messiah will have some role in the gathering of the exiles back into the

land, the rebuilding of Jerusalem and the Temple. He will create the conditions in which Israel can learn and do Torah and inherit its promised blessings. He is a primary focus of creation, and all

the prophets spoke of his reign. He will redeem Israel en masse but not those who have separated themselves from Israel. How long he will reign is an open question.

The Messiah will be suddenly revealed, and already is in waiting behind the scenes.

Three things come unawares: the Messiah, a found article, and a scorpion. (Sanh. 97a. in Scholem 1971:11)

It is not possible to tell the time when Messiah will be revealed. If Israel would repent even for a single day, they would be instantly redeemed and the Son of David would instantly come, for it says (Ps. 95:7): Today if you will listen to his voice." (Midrash Rabbah, Exodus 25:16).

Jacob Neusner summarises:

'The Messiah' is an all but blank screen onto which a given community would project its concerns. (Neusner 1984:xi)

The coming of the Messiah can occur in several ways. It is preceded by disasters and horrors, the birth-pangs of the Messiah (hevlei ha-mashiach). The Messiah is hidden until the last possible

moment, when things can not get any worse, and then makes his appearance. The old world disappears in the catastrophe and the new age dawns. Alternatively he appears to lead Israel in battle, to

defeat her enemies, and inaugurates a Messianic age which is an intermediate state preceding the world to come. His coming is the sign that the Last Judgment is at hand, and the redemption of this

world of darkness is about to dawn.

The classic statement of this is the Messiah hiding among the lepers at the gates of Rome.

R. Joshua b. Levi met Elijah standing by the entrance of R. Simeon b. Yohai's tomb... He then asked him, 'When will the Messiah come?' — 'Go and ask him himself,' was his reply. 'Where is he sitting?' — 'At the entrance (of Rome).' And by what sign may I recognize him?' — 'He is sitting among the poor lepers: all of them untie [them] all at once, and rebandage them together, whereas he unties and rebandages each separately, [before treating the next], thinking, should I be wanted, [it being time for my appearance as the Messiah] I must not be delayed [through having to bandage a number of sores].' So he went to him... 'When wilt thou come Master?' asked he, 'Today', was his answer. On his returning to Elijah, the latter enquired, 'What did he say to thee?' ... 'He spoke falsely to me,' he rejoined, 'stating that he would come today, but has not.' He [Elijah] answered, 'This is what he said to thee, Today, if ye will hear his voice' (Psalm 95:7) (B. Sanh. 98a).

From such various streams medieval speculation grows, some mystical and otherworldly, some rationalistic and evolutionary. Maimonides speculates that the Messiah is not a figure who will perform great miracles, but by the extent to which he succeeds in his worldly mission of regathering the exiles, rebuilding the temple, and re-instituting the Torah. The only utopian element in an otherwise rationalist perspective is that all humanity will recognise the God of Israel. (Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Melakim, 11-12: Commentary on Mishnah Sanhedrin 10).

Article 12 of the Maimonides' Thirteen Articles of Faith states: I believe with complete faith in the coming of Messiah, and even if he may tarry, nevertheless, I will await his coming every day.

The King Messiah is destined to stand and restore the kingdom of David to its former glory, and build the Holy Temple, and gather the dispersed of Israel, and all of the ordinances (of the Torah) will return in his days to what they were before, sacrificing sacrifices, observing the years of release and jubilees accor¬ding to all their commands given in the Torah. And whoever does not believe in him, or whoever does not wait for his coming, does not reject only the proph¬ets, but also the Torah and Moses our Rabbi, since the Torah bears witness to him, as it is written, "And the L-rd your G-d will restore your fortunes, and have compassion on you, and come back and gather you... If you are dispersed to the ends of the heavens... the L-rd will bring you..." (Deuteronomy 30:3-4).

And these things that are expounded in the Torah include all the things spoken by all of the prophets.

Gershon Scholem describes how the deep feeling of the impossibility of calculating the Messianic Age produced the idea of the hiddenness of the Messiah. He is already present somewhere and according

to legend, was born on the day of the destruction of the Temple. At the moment of the deepest catastrophe there exists the chance for redemption.

Israel speaks to God: when will you redeem us? He answers: when you have sunk to the lowest level, at that time I will redeem you. (Midrash Tehillim to Ps. 45:3).

Corresponding to this 'continually present possibility' is the concept of the Messiah who 'continually waits in hiding'. It takes many forms, the most striking of which places him at the gates of Rome, living among the lepers and beggars of the Eternal City (Sanh. 98a). This truly staggering 'rabbinic fable' stems from the second century, long before the Rome which has just destroyed the Temple and driven Israel into exile itself becomes the seat of the Vicar of Christ and of a Church seeking dominion by its claim to Messianic fulfilment. The ninth century apocryphal work the Sefer Zerubbabel similarly places the Messiah at the Gates of Rome.

I asked 'What is the name of this place?' And he [God] said to me: 'This is Great Rome, in which I am kept captive until my end comes.'... And I said: 'I have heard your tidings, that you are the Messiah of my God.' And I said to him: 'When will the lamp of Israel light up?' And as I said these words, and lo, a man with wings [Metatron] came to me and said to me that he was the celestial prince of the army of Israel who fought against Sanherib and the kings of Canaan, and will in the future fight the war of the Lord with the Messiah of the Lord against the insolent king, Armilus, son of the stone, who will issue from the stone... And he said to me: 'This is the Messiah of the Lord, who is hidden here until the time of the End...' (Sefer Zerub¬babel, BhM 2:54-55 in Patai 1979: 111).

This symbolic antithesis between the true Messiah sitting at the gates of Rome and the head of Christendom, who reigns there, accompanies Jewish Messianic thought through the centuries. And more than once we learn that Messianic aspirants have made a pilgrimage to Rome in order to sit by the bridge in front of the Castel Sant' Angelo and this enact this symbolic ritual. (Scholem 1971:12).

The hidden Messiah of the Passover Hagaddah

Like the Redemption that is as yet hidden, so is the Afikomen hidden at the beginning of the feast. It ‘alludes to the meal that the holy one, blessed be He is to make in the future for the righteous’ (Hayyim ben Abraham ha-Cohen, Tur Bareket [Amsterdam 1653:477; 83b] in Yuval 2006:242). Yuval is not the first to point out the Messianic overtones of the Afikomen (David Daube preceded him), but gives the historical basis for the development of the Haggadah in the light of both Christian and Jewish Messianic understanding.

The Afikomen is wrapped in a shroud before it is revealed. ‘One should not ignore the phenomenological similarity between the various stages of the afikomen ceremony and the Crucifixion of Yeshua (Jesus), his being enwrapped in a shroud, his being placed in a closed cave, until at the climax, on Easter Sunday, he is risen from the dead.’ (Yuval 2006:244).

In the 17th century there was a custom of piercing a piece of the afikoman and hanging it on the wall:

Upon their houses, opposite the door, the Jews place a black spot on a white wall so that it will be visible to all, young and old, and so they will not forget their God and the Temple, and over this they pray a special prayer. Similarly, on Passover they bake round cakes on un leavened dough, bless it, and nail it over the black spot, in memory of God’ (Yuval 245).

The matzah, the symbol of redemption, is attached to the empty spot on the wall intended to commemorate the Destruction of the Temple. Yuval notes the parallels with Communion.

They eat the hidden piece of matzah at the end of the meal after completing the reading of the Haggadah, and they consider it most holy. Therefore, they are careful not to let any crumb of it fall on their beards, on the floor, or in any other place. They say that this matzah is instead of the Paschal Lamb, and therefore they hide it, like their Messiah, the time of whose coming is hidden away. (Der Ganze Jüdische Glaube, Frankfurt, 1689: 54 ).

It seems to me (Yuval) that what we have here is a ‘Jewish internalisation of Christian ritual language. The Christians eat matzah all year long, during communion, while the Jews eat it only once a year, at Passover (Yuval 2006: 241).

The afikomen still retains its Messianic symbolism in Judaism. Rabbi Shulweiss reflects on ‘Wanting Wholeness But Not Having It’: In the outline of the seder ritual, the division of the middle matzah--yahatz-takes place early, before the great declaration, “This is the bread of affliction.” The eating of the retrieved matzah comes after ransoming it from the children at the end of the seder. The ritual of eating the afikoman is called tzafun, which means “hidden.” It, too, is eaten in silence, without benediction, before midnight. After the afikoman, no food or drink is to be taken except for the final two cups of wine. In some haggadot there is a devotional prayer in Aramaic that announces, “I am ready and pre-pared to perform the commandment of eating the afikoman to unite the Holy One blessed be He and His Divine Presence through the hidden and secret Guardian on behalf of all Israel.”

Brokenness is a symbol of incompletion. Life is not whole. The Passover itself is not complete. The Passover we celebrate deals with the past redemption of our people from the bondage in Egypt. That redemption is a fact of history and it heartens us because through its recollection we know that our hope for future redemption is not fantasy. It did happen once and to our whole people. A small slave people witnessed the power of a supreme divine agency to snap the heavy chains around our hands, and to break the yoke upon our necks. It was no dream, this redemption. It happened, and at the Seder we relate the testimony of this act.

But it is toward the Passover of the Future that our memories are directed. The redemption is not over. There is fear and poverty and sickness. There is a trembling on earth. Around us are the plagues of pollution, and images of fiery nuclear explosions in the clouds, not like the cloud of glory and the pillar of fire that led our ancestors through the wilderness. The broken matzah speaks to our times, shakes us by the shoulders and shouts into our hearts, “Do not bury your spirit in history. Do not think it is over, complete, that the Messiah has come and you have nothing to do but to wait, to pray, to believe”. (Shulweiss 1986: 5)

In the Middle Ages the diversity of views held about Israel’s redemption persisted. Maimonides rationalist position held the restorative view that the Messiah, without miracles or wonders, would signal the end of foreign domination of Israel.

Nahmanides echoed this: ‘ our Law and Truth and Justice are not dependent on a Messiah’ (Enc. Jud. 11:1263). However, the apocalyptic expectations continued, and the non-rationalist stream of medieval Judaism that led to the Jewish mystical tradition had great urgency and immediacy. False Messiahs appeared. But even when they were proved by events to be false, nevertheless they may have been still be the true Messiah. Perhaps they were in a state of ‘hiddenness’ in which only their most devoted and faithful disciples could understand the nature of their mission and their true identity. From this derives the doctrine of the ‘occultation of the Messiah.’

The occultation of false Messiahs

In 1648 Shabbetai proclaimed himself the Messiah, married the Torah and celebrated all the Jewish festivals in one week. Although Redemption did not occur his followers grew, and bets were taken on the London Stock Exchange about the success of his claims. He was banned by most Rabbis, but one, Nathan of Gaza, confirmed his Messiahship. By 1665 much of world Jewry looked for redemption in this Turkish-born messiah. They prepared to emigrate to Israel, sold their possessions and stopped work. Then came the disillusionment of Zvi’s arrest by the Turkish Sultan and conversion to Islam under threat of death. His core followers were disappointed and distraught, but explained the extraordinary events as the ‘birth-pangs the messiah’. Mystical interpretations of Zvi’s apostasy continued, existing in the Donmeh sect until the present.

The Sabbatian doctrine of occultation (hith‛allemuth, he‛lem, Gk. ’αφανισµος) was not borrowed from other systems but according to Scholem was the result of similar structures of faith. Scholem links it to the cult of apotheosis of Roman emperors. The hero of this process is one ‘who, by the grace of God, is liberated from death at the very moment of death, and is removed to Paradise, Heaven, or a distant land where he continues to live in the body.’ (Elias Bickerman, Das Leere Grab, ZNW, XX111 (1924), 285 in Scholem 1973: 923). The Sabbatian doctrine of occultation was revealed to Rabbi Nathan by the celestial messengers Joshua and Caleb that ‘AMIRAH (our Lord and King, may his Majesty be exalted.) was exalted and hidden, body and soul, on the Day of Atonement, at the time of ne‛ilah.

‘Whoever thinks that he died like all men and his spirit returned to God commits a grave sin.’

The Kabbalistic doctrine of occultation was developed further. Shabbetai had ascended to and been absorbed into the ‘supernal lights’. A more popular legend arose:

‘Our Lord has gone to our brethren, the children of Israel, the Ten Tribes that are beyond the river Sambatyon, in order to marry the daughter of Moses. If we are worthy, he will return at once after the wedding celebrations to redeem us; if not, then he will tarry there until we are visited by many tribulations.’ (Baruch of Arezzo in Scholem 1973: 924).

Nathan continued to preach that Shabbetai was alive until his own death in 1680. He celebrated the 4th meal after Sabbath (early morning, Sunday) as ‘the meal of the king messiah’’. He pronounced that ‘a man who busies himself with matters pertaining to AMIRAH, even by telling stories only, is considered like one who studies the mysteries of the merkabah.’ (Scholem 1973: 925).

The Messiah had not really ‘died,’ he had only ‘gone into occultation.’ In any case, the doctrine of reincarnation, as it was commonly accepted by the Kabbalists, allowed the supposition that the Messiah wandered through many forms from Adam down to His most recent one (AdAM – Adam – David -Messiah). In the nineteenth century the Donmeh assumed eighteen such reincarnations of the soul of Adam and the Messiah. (Scholem 1995: 146).

Menachem Mendel Schneerson

Similarly, and more recently, the doctrine of occultation has been applied to the Lubavitcher Rebbe.

Unlike Shabbetai Zevi, Menachem Schneerson never expressly proclaimed himself as Messiah. However, he did not always discourage his followers from proclaiming him as such. As he neared death he suggested obliquely that he was the promised Redeemer. In April, 1991, the Rebbe made a speech that has posthumously been interpreted as the Rebbe's self-proclamation of Messiahship.

He stated that he had done all he could to spur Jews to work actively for the messianic redemption, and he urged his followers to do the rest. He said, “Now do everything you can to bring Moshiach, here and now, immediately.” On another occasion he said that “Messiah is already here and that the process of redemption is beginning to unfold.” Although these pronouncements may be less than clear in the ears of non-messianists, they apparently excited a fervour for “Moshiach Now” in the hearts of the Rebbe's followers.

‘We haven't been wrong [in identifying the Rebbe as the Messiah.] We have only been wrong in assuming that this is going to happen in the Rebbe's lifetime... So we were wrong in the calculation of the timing (see Klayman 2005 for full references).

The belief that the Rebbe would accomplish the redemption of his people before he would die then changed in the light of his death. A couple of adherents stated that “the way we understood there would not be a period of no life [that is the Rebbe would not die], on these things we were wrong.”

Shortly after the Rebbe died his followers began to rationalize his death. Some refused to believe that he was dead; in fact, some insisted that he was not really in the coffin. Others said that he was in a condition of suspension and that it was just that his body was dormant but his spirit was with them. Still for others, there was the understanding that the Rebbe “lives and exists among us now exactly as he did before, literally.”

Five days after his death, statements came forth that the Rebbe would resurrect and lead the Jewish people to redemption. They continued to insist that he would soon rise, and still the messianists, after ten years, do not light a yartzheit candle for him, nor have they replaced him with an eighth rebbe.

Max Kohanzad, who surveyed the Messianic doctrine of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, has written:

In short, then, the Rebbe could hardly have been more direct about his own messianic claims. If the Messiah is:

- The Lubavitcher Rebbe of the generation,

- The seventh leader of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement, who directly followed the Previous Rebbe,

- The individual who announces ‘Humble ones…’,

- The third in line after Rabbi Dov Baer and Yoseph Yitzchak

- The individual whose house is at 770 Eastern Parkway,

- Whose name is Menachem, then there is clearly only one candidate!

- To make matters even clearer, the Rebbe on occasions even said to his audience that

- ‘Moshiach is here in this room, in front of you... all you have to do is open your eyes!’ (Kohanzad 2005: ch. 6: 25)

His Messiahship was pronounced and the Maimonidean criteria have been reformulated to accommodate the fulfilment of the Rebbe as Messiah. All of these rationalizations exist in the face of traditional Jewish understanding that a messiah who dies in the midst of his redemptive mission, is no messiah.

The Hidden Messiah of Two-Covenant Theology

For Franz Rosenzweig, the author of The Star of Redemption, the Messiah plays a vital role. At one time Rosenzweig was on the point of becoming a Christian, but instead developed a ‘star of David’ structure to his philosophy which relates God, humanity and the world to Creation, Revelation, Redemption. His complex work, written on postcards to his mother from the trenches of WW1, has influenced Jewish-Christian relations by articulating the ‘Two Covenant’ theory of salvation, which has been developed by many Christian theologians. Rosenzweig died in 1939, with his project incomplete, but leaving a legacy taken up by others. Rosenzweig conceives of all Jewish history ‘messianically’. His Messiah stands ready at the end of time, to redeem the world. But this Messiah, who ‘waits and wanders, and grows eternally’ is not Yeshua (Jesus).

Over against Israel, eternally loved by God and faithful and perfect in eternity, stands he who is eternally to come, who waits and wanders, and grows eternally – the Messiah. Over against the man of earliest beginnings, against Adam the son of man, stands the man of endings, the son of David the king. Over against him who was created from the stuff of the earth and the breath of the mouth of God, is the descendant from the stem of anointed kings; over against the patriarch, the latest offspring, over against the first, who draws about him the mantle of divine love, the last, from whom salvation issues forth to the ends of the earth; over against the first miracles, the last, which – so it is said – will be greater than the first. (Rosenzweig 1970: 307).

Rosenzweig’s decision not to become a Christian, his understanding of philosophy and history, and his own personal faith, led him to the view that whilst Christianity brought the nations to God, the Jewish people were already with God. His commentary on John 14:6 is amended:

No one comes to the father [except through the son] – but it is otherwise if someone no longer needs to come to the father because he is already with him. And this is the case for the people of Israel…(Hollander 2004:3)

Israel is already with God, and her life on earth as the people of God consists in anticipating and pre-empting the end of Time and Creation in a new Creation. Israel herself thus has a messianic role, and the Messiah is hidden within her peoplehood, and awaits to fulfilment of her destiny.

Rosenzwieg died just before the full horrors of the Holocaust, but post-Holocaust Christian theologians have incorporate his views, calling for an end to the triumphalism that proclaims the Christian Christ who has already come rather than the Jewish Messiah who has yet to appear.. Rosenzweig’s hidden Messiah is found within the mission and destiny of Israel, which is set against that of the Church.

The hidden Messiah of Auschwitz

As Jewish theologians have contemplated the horrors of the Holocaust two in particular have linked this with the Messiah hidden in the sufferings of the Jewish people, and in the Hiddenness of God. Ignaz Maybaum, the British Reform theolo¬gian, lost his mother and two sisters in the Holocaust. He came to Britain after the war, and wrote The Face of God after Auschwitz, pondering the mystery of the Holocaust. For Maybaum, the Holocaust was the result of divine providence, not as an act of judgment on the Jewish people, but rather because they were chosen by God to be the sacrificial victims to bring about God's purposes for the nations in the modern world.

Like two other events in Jewish history, the Holocaust is a third act of churban, (herev – sword) where God uses an event of utter destructiveness to cut out a part from the body of humanity so that

a new stage of healing and renewal may begin. The fall of Jerusalem and exile to Babylon in 586 enabled the Jewish community to bring knowledge of God and Torah to the nations, and was an act of

creative destruction brought about by divine providence. The destruction of Herod's Temple established the worship of the Synagogue and the spreading of ethical monotheism in the Greco-Roman world. A

churban ends an old era and inaugurates a new period of renewal, achieving progress through sacrifice (Cohn-Sherbok 1989:29).

Like Pharaoh, Nebuchadnezzar, and Vespasian, even Hitler was an unwitting and unworthy servant of God. God 'used this instrument to purify, to punish a sinful world: the six million Jews, they died an innocent death; the died because of the sin of others.' (Maybaum in Cohn-Sherbok 1989:30). The Jewish people are the Suffering Servant of Isaiah 53, and the surviving Remnant must purify themselves, especially from hatred in response to those who perpetrated the Holocaust, as they enter a new era of justice, mercy and peace.

In Auschwitz Jews suffered vicarious death for the sins of mankind. ...Can any martyr be a more innocent sin-offering than those murdered in Auschwitz! The millions who died in Auschwitz died 'because of the sins of others.' Jews and non-Jews died in Auschwitz, but the Jew-hatred which Hitler inherited from the medieval Church made Auschwitz the twentieth century Calvary of the Jewish people. (Maybaum 1965:35)

The Messiah will only come at a time of destruction. When the Messiah is to come, the House of Learning will be a place of fornication, Gallilee will be devastated, people will wander from town to town but find no compassion, the wisdom of the rabbis will decay, the pious will be despised, charity will not be found, and truth will be absent (Mishna Sota 14, in Maybaum 1965: 33)

The Jewish people are the hidden corporate Messiah who are revealed when God sends them to crucifixion to bring the nations to a new righteousness. Their suffering is the Calvary of the 20th century. The Golgotha of modern mankind is Auschwitz. The Cross, the Roman gallows, was replaced by the gas chamber. The gentiles, it seems, must first be terrified by the blood of the sacri¬ficed scapegoat to have the mercy of God revealed to them and become con¬verted, become baptised gentiles, beco¬me Christians. (Maybaum 1965: 36).

Maybaum develops the traditional teaching that the Messiah is none other than Israel personified. Maybaum's Messiah hidden in the sufferings of the Jewish people is not without problems. His suffering servant Israel dies at the will of a God who does not appear all-loving and all powerful, but allows evil and cruelty to achieve His ends. The Jewish people were not willing mar¬tyrs, and it is unclear what new righteous¬ness was achieved in the period following the churban. But his theology points to a Messiah hidden in and identified as the Jewish people, and to this we shall return.

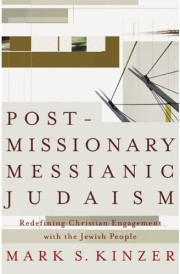

Mark Kinzer's "Post Missionary Messianic Judaism"

Mark Kinzer’s Postmissionary Messianic Judaism proposes that the Yeshua (Jesus) the Messiah is hidden in the midst of the Jewish people. Kinzer proposes a ‘bilateral ecclesiology’ made up of two distinct but united communal entities:

The community of Jewish Yeshua-believers, maintaining their participation in the wider Jewish community and their faithful observance of traditional Jewish practice, and

The community of Gentile Yeshua-believers, free from Jewish Torah-observance yet bound to Israel through union with Israel’s Messiah, and through union with the Jewish ekklesia.

Kinzer’s stresses on the inherent ‘twofold nature’ of the ekklesia preserves ‘in communal form the distinction between Jew and Gentile while removing the mistrust and hostility that turned the distinction into a wall’. Kinzer argues that a bilateral ecclesiology is required if the Gentile ekklesia is to claim rightfully a share in Israel’s inheritance without compromising Israel’s integrity or Yeshua’s centrality.

In Chapter Six Kinzer turns to the Jewish people’s apparent “no” to its own Messiah. Kinzer argues that Paul sees this rejection as ‘in part providential, an act of divine hardening effected for the sake of the Gentiles’. Paul, according to Kinzer, even implies that this hardening involves Israel’s mysterious participation in the suffering and death of the Messiah.

In the light of Christian anitsemitism and supersessionism, the Church’s message of the Gospel comes to the Jewish people accompanied by the demand to renounce Jewish identity, and thereby violate the ancestral covenant. From this point onward the apparent Jewish “no” to Yeshua expresses Israel’s passionate “yes” to God – a “yes” which eventually leads many Jews on the way of martyrdom. Jews thus found themselves imitating Yeshua through denying Yeshua (Jesus)! If the Church’s actual rejection of Israel did not nullify her standing nor invalidate her spiritual riches, how much more should this be the case with Israel’s apparent rejection of Yeshua! (Kinzer 2004:5).

The Jewish people’s apparent ‘no’ to Yeshua (Jesus) does not rule them out of God’s salvation purposes, any more than the Church’s actual ‘no’ to the election of Israel. Both are within the one people of God, although there is a schism between them. The New Testament ‘affirms the validity of what we would today call Judaism’ (Kinzer 2005:215).

Kinzer recognises that the presence of Yeshua is necessary in order to affirm Judaism.

Those who embrace the faith taught by the disciples will be justifiably reluctant to acknowledge the legitimacy of a religion from which Yeshua, the incarnate Word, is absent (Kinzer 2005:217).

Judaism’s validity can not demonstrated if Jewish people have a way to God that ‘bypasses Yeshua.’ However, Kinzer argues that in some mysterious and hidden way ‘Yeshua abides in the midst of the Jewish people and its religious tradition, despite that tradition’s apparent refusal to accept his claims’ (Kinzer 2005: 217). This divinely willed ‘disharmony between the order of knowing and the order of being’ means that Yeshua is present with his people without being recognised. The ontic is to be distinguished from the noetic, what exists from what is known. The New Testament affirms that Yeshua is the representative and individual embodiment of the entire people of Israel, even if Israel does not recognise Yeshua and repudiates his claims. Even this rejection testifies to his status as the despised and rejected servant. Echoing Karl Barth’s doctrine of the Church in relation to Israel, Israel’s ‘no’ is answered by the Church’s ‘yes’ to Yeshua (Jesus), and in Yeshua (Jesus) himself both ‘yes’ and ‘no’ are brought together, just as Yeshua (Jesus) is both divine and human, and accepted and rejected.

Both church and Israel are ‘bound indissolubly to the person of the Messiah’, one in belief, the other in unbelief. Therefore ‘Israel’s no to Yeshua can be properly viewed as a form of participation in Yeshua!’ (Kinzer 2005:223).

If the obedience of Yeshua that led him to death on the cross is rightly interpreted as the perfect embodiment and realisation of Israel’s covenant fidelity, then Jewish rejection of the church’s message in the second century and afterward can rightly be seen as a hidden participation in the obedience of Israel’s Messiah (Kinzer 2005:225).

This sounds decidedly paradoxical. How are we to understand and respond to it? Kinzer’s argument draws from earlier thinkers like Lev Gillet, the friend of Paul Levertoff.

His entire notion of “communion in the Messiah” presumes that faithful Jews and faithful Christians can have communion together in the one Messiah. In fact, he seems to hold that the Messiah is also hidden for Christians to the extent that they fail to understand or acknowledge the ongoing significance of the Jewish people in the divine purpose. (Kinzer 2007:1)

Gillet views the Jewish people as a ‘corpus mysticum – a mystical body, like the church.’ (Kinzer 2005: 280). The suffering of the Jewish people is to be understood in the light of Isaiah 53, as both ‘prophetic and redemptive,’ but Gillet does not, according to Kinzer, lose ‘his christological bearings’ (:281). Gillet’s aim is to build a ‘bridge theology’ that links the mystical body of Christ with that of the mystical body of Israel.

The corpus mysticum Christi is not a metaphor; it is an organic and invisible reality. But the theology of the Body of Christ should be linked with a theology of the mystical body of Israel. This is one of the deepest and most beautiful tasks of a ‘bridge theology’ between Judaism and Christianity. (Gillet 1942:215 in Kinzer 2005: 281)

Gillet aims to heal the schism between Israel and the Church, showing that both Christian and Jew are united in the Messiah.

The idea of our membership in Israel has an immediate application in al the modern questions concerning Jewry. If we seriously admit the mystical bond which ties us, as Christians, to the community of Israel, if we feel ourselves true Israelites, our whole outlook may be modified, and our lives of practical action as well. (Gillet 1942: 215)

However, Gillet’s argument relies on a ‘the mystery of the [future] restoration of Israel, who are still, in Paul’s words, experiencing ‘Blindness in part’. (ibid.) The Messiah is hidden from them, because of the blindness of unbelief. Whilst He is hidden within His people, he is also hidden from them by their partial hardening.

Kinzer’s concept of the ‘hidden Messiah’ derives not from the anonymous Christianity of the Roman Catholic theologian Karl Rahner, but from Karl Barth and Franz Rosenzweig, and later Jewish-Christian relations thinkers such as Paul van Buren. Kinzer also refers to Edith Stein, the Jewish philosopher who became a Carmelite nun, who saw the sufferings of the Jewish people as ‘participating in the sufferings of their unrecognised Messiah’ (Kinzer 2005: 227).

Thomas Torrance lends support to this Christological understanding of the suffering of Israel as participation in the suffering of the Messiah, albeit unconsciously.

Certainly, the fearful holocaust of six million Jews in the concentration camps of Europe, in which Israel seems to have been made a burnt-offering laden with the guilt of humanity, has begun to open Christian eyes to a new appreciation of the vicarious role of Israel in the mediation of God’s reconciling purpose in the dark underground of conflicting forces within the human race. Now we see Israel, however, not just as the scapegoat, thrust out of sight into the despised ghettos of the nations, bearing in diaspora the reproach of the Messiah, but Israel drawn into the very heart and centre of Calvary as never before since the crucifixion of Yeshua (Jesus). (Thomas Torrance, The Mediation of Christ (Colorado Springs: Helmers and Howard, 1992), 38-39, in Kinzer 227).

Kinzer echoes Protestant theologian Bruce Marshall in arguing that the Jewishness of Yeshua (Jesus) implies his continuing membership of and participation in the Jewish people. God’s incarnate presence in Yeshua thus ‘resembles Gods presence among Yeshua’s flesh-and-blood brothers and sisters’ (Kinzer 2005:231). Quoting Bruce Marshall, the doctrine of the incarnation of God in Christ is analogous to the doctrine of God indwelling Carnal Israel, as articulated by Michael Wyschogrod, the Jewish thinker.

The Christian doctrine of the incarnation is an intensification, not a repudiation, of traditional Jewish teaching about the dwelling of the divine presence in the midst of Israel (Marshall 2000:178 in Kinzer 2005:231).

If God is ‘present in Israel, Yeshua is also present there’, and according to Robert Jenson, the ‘church is the body of Christ only in association with the Jewish people’.

Can there be a present body of the risen Jew, Yeshua (Jesus) of Nazareth, in which the lineage of Abraham and Sarah so vanishes into a congregation of gentiles as it does in the church? My final – and perhaps most radical – suggestion to Christian theology… is that… the embodiment of the risen Christ is whole only in the form of the church and an identifiable community of Abraham and Sarah’s descendants. The church and the synagogue are together and only together the present availability to the world of the risen Yeshua (Jesus) Christ. (Jenson 2003:13 in Kinzer 2005:232).

Kinzer is covering much new ground here, painting in broad brushstrokes an ecclesiology developed by postliberal Christian theologians in dialogue with contemporary Jewish thinkers. Much of the discussion draws from Karl Barth’s Christological doctrine of the election of the one ‘community of God’ as Church and Israel, and the doctrine runs the same risks of universalism on the one hand, and a continuing supersessionism on the other. Whilst Karl Barth withdrew from participation in Rosenzweig’s ‘Patmos group’ because of its perceived Gnosticism, there is also a danger of Gnosticism in this doctrine of the Hidden Messiah incarnate in his people Israel (Lindsay 2007:28). Kinzer relies on a ‘divinely willed disharmony between the ontic and the noetic, following Bruce Marshall.

For most Jews, Paul seems to say, there is at this point a divinely willed disharmony between the order of knowing and the order of being which will only be overcome at the end of time. (Kinzer 2007:1)

But if the mystery of God’s dwelling in Christ is known to the Church, it cannot be equally true that Israel can know that the opposite is the case, and that Yeshua (Jesus) is not the risen Messiah. Whilst Christians recognise a continuing election of Israel (the Jewish people) and thus a continuing commitment of Yeshua (Jesus) to His people, they will be reluctant to admit that this commitment in itself is salvific, or that the hidden presence of the Messiah with His people is the means by which he is revealed to them. The Hidden Messiah of PMJ owes more to a Christian re-orientation of perspective on Yeshua (Jesus) and the election of Israel than on a Jewish recognition of a hidden Messiah. The hidden Messiah of PMJ is more a Christian re-evaluation of the presence of Christ within the Jewish people than a Jewish recognition of the Messianic claims of Yeshua (Jesus).

The hidden Messiah of the Lausanne Consultation on Jewish Evangelism (LCJE )

A venerable Jewish anecdote describes a man hired by his shtetl to sit at the outskirts of town and alert his village should he see the Messiah coming. When asked why he had accepted such a monotonous form of employment the watchman would invariably reply: ‘The pay is not so good, but it’s a lifetime job.’ Judaism considers waiting for the redeemer a lifetime job, and Jewish people are obligated not only to believe in the coming of the Messiah but also to yearn for his coming (Soloveitchik 2004:1)

But waiting and yearning are not enough. We are here today to put the watchman out of business by announcing that the Messiah is here, and is no longer hidden. We can recognise Him now, and know His presence with us. It may still be a lifetime job (unless He returns first), but the job has changed from being a watchman to being a herald of Good News. We need to change the job description, or we will be keeping the Messiah hidden from His people.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church states:

And when one considers the future, God’s People of the Old Covenant and the new People of God tend toward similar goals: Expectation of the coming (or the return) of the messiah. But one awaits the return of the messiah who died and rose from the dead and is recognized as Lord and Son of God; the other awaits the coming of a messiah, whose features remain hidden till the end of time; and the latter waiting is accompanied by the drama of not knowing or of misunderstanding Christ Yeshua (Jesus). (Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraph 840).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ben Sasson, H. H. 'Messianic Movements.' In Encyclopaedia Judaica, vol. 11, 1417-1427.col. 1263.

Berger, David. The Rebbe, The Messiah and the Scandal of Orthodox Indifference. Oxford: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2001.

Blevins, James L. The Messianic Secret in Markan Research, 1901-1976. Washington, D. C.: University

Press of America, 1981.

Cohn-Sherbok, Dan. Holocaust Theology. London: Marshall, Morgan and Scott, 1989.

———. The Jewish Messiah. Edinburgh: T and T Clark, 1997. Green, William Scott and Jed Silversteen, 'The Doctrine of the Messiah.' In

The Blackwell Companion to Judaism, edited by Jacob Neusner and Alan J. Avery-Peck, 247-267. Blackwell, Oxford, 2003.

Hollander, Dana. 'On the Significance of the Messianic Idea in Rosenzweig.' Cross Currents (January 2004). http://www.encyclopaedia.com/print able.aspx?id=1G1:114975243

Kinzer, Mark S. Postmissionary Messianic Judaism: Redefining Christian Engagement with the Jewish People. Grand Rapids: Brazos, 2005.

Klayman, Elliot. 'Does The Lubavitcher Rebbe Fit The Festinger Model?' Kesher 18 (Winter 2005). http://www.kesherjournal.com

Kohanzad, Max. The Messianic Doctrine of the Lubavitcher Rebbe. E-book available at http://www.lulu.com, 2007.

Lindsay, Mark R. Barth, Israel and Yeshua (Jesus): Karl Barth's Theology of Israel. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007.

Marcus, Joel. 'The Once and Future Messiah in Early Christianity and Chabad.' New Testament Studies 47, no. 3 (July 2001), 381-401.

Marshall,Bruce. Trinity and Truth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Maybaum, Ignaz. The Face of God after Auschwitz. Amsterdam: Polak and Van Gennep, 1965.

Mowinckel, Sigmund, He That Cometh: The Messiah Concept in the Old Testament and Later Judaism. Translated by G. W. Anderson. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005.

Neusner, Jacob. Messiah in Context: Israel's History and Destiny in

Formative Judaism. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1984.

Patai, Raphael. The Messiah Texts: Jewish Legends of Three Thousand Years. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1979.

Pollefeyt, Didier. 'Christology after Auschwitz: A Catholic Perspective.' JEWS OF EURO-ASIA 1 (January-March 2005). http://www.eajc.org/publish_gen_e. php?rowid=98

Rosenzweig, Franz. The Star of Redemption. Translated from the 2nd edition of 1930 by William W. Hallo. Notre Dame, Notre Dame Press, 1970. Reprint 1985.s

Scholem, Gershon. The Messianic Idea in Judaism. New York: Schocken, 1995. ———. Shabbetai Sevi: The Mystical Messiah. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1973.

Schulweis Harold A. The Hidden Matzah: Spiritual Perspective. Sh'ma: A Journal of Jewish Responsibility, May 1986.

Soloveitchik, Meir. 'Redemption and the Power of Man.' Azure 16 (Winter 2004). http://www.azure.org.il/magazine/magazine.asp?id=172

Torrance, Thomas The Mediation of Christ . Colorado Springs: Helmers and Howard, 1992.

Watson, David. 'The Messianic Secret in Mark.' http://people.smu.edu/dwatson/messsianic_secret_001.htm (accessed March 10, 2007)

Wrede, William. The Messianic Secret. Trans. J. C. G. Greig. Cambridge and London: James Clarke & Co. Ltd, 1971.

Yuval, Israel Jacob. Two Nations in Your Womb: Perceptions of Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

Comments

-

Judaism's view of the Messiah differs substantially from the Christian idea of the Messiah. In the Jewish account, the Messiah's task is to bring in the Messianic age, a one-time event, and a

presumed messiah who is killed before completing the task (i.e., compelling all of Israel to walk in the way of Torah, repairing the breaches in observance, fighting the wars of God -

Thank you, Richard, for a superb synopsis on the topic. The hidden Messiah of the Mishnaic system and of Talmudic speculation was of most value to me because you provided references to key texts

which would not easily be found otherwise.